In a recent post I explained the term Absorbent Mind. In this week’s post we will explore another common phrase that is heard in relation to Montessori education: the sensitive periods.

Hugo de Vries (Dutch botanist and geneticist) detected the sensitive periods through his research with animals, but Montessori declared that she and her fellow educators discovered it to be true of children as well, utilising it for improving teaching (M. Montessori, 1966). The sensitive periods in a child’s development establish and control each developmental plane, and are inextricably linked to all other aspects of the child’s development, including internal and external growth (Grazzini, 1979; M. Montessori, 1966; The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008; Zener, 2003). Furthermore, the importance of early learning experiences is recognised in brain research due to the neural connections made during the sensitive periods (The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008). Montessori (1966) described the concept thus:

A sensitive period refers to a special sensibility which a creature acquires in its infantile state, while it is still in a process of evolution. It is a transient disposition and limited to the acquisition of a particular trait. Once this trait, or characteristic, has been acquired, the special sensibility disappears. Every specific characteristic of a living creature is thus attained through the help of a passing impulse or potency. (M. Montessori, 1966, p. 38)

Thus, in connection to the development of a child, they have an innate impulse that drives them to carry out certain acts at certain developmental times (M. Montessori, 1966; The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008; Zener, 2003). However, Montessori (1966) noted that if a child is unable to act on the impulses of that sensitive period the chance for a “natural conquest” (p.39) will be gone forever. Obstacles to learning or stressful experiences during these times can create a strong negative reaction, as can sometimes be seen in tantrums in the very young child (M. Montessori, 1966; The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008).

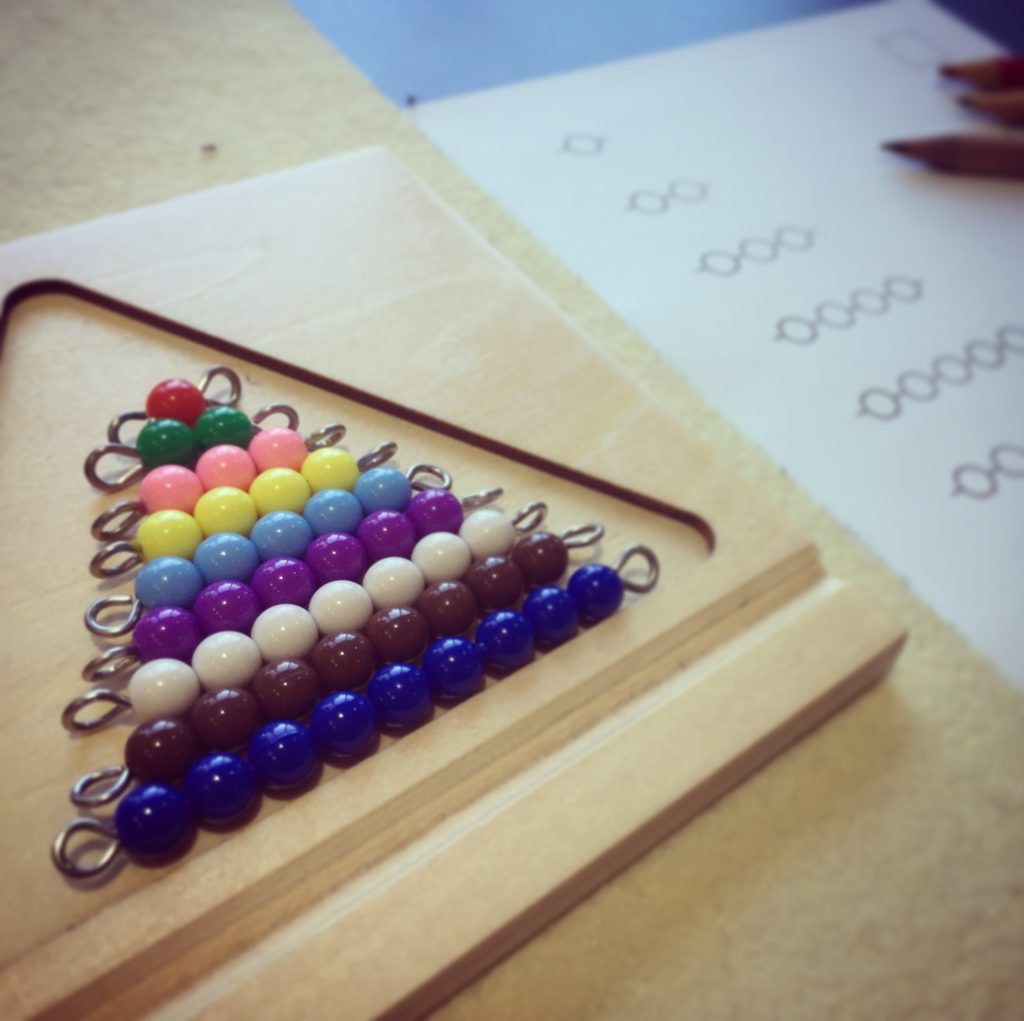

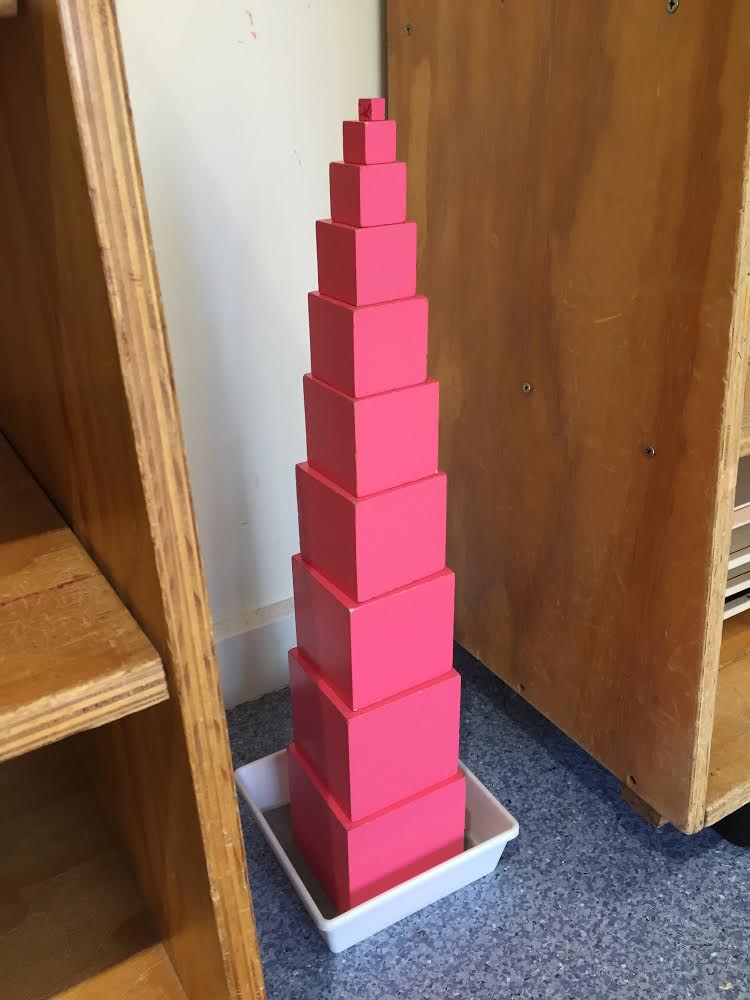

The learning experiences during these sensitive periods play a vital role in a person’s neural development (The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008). During the sensitive periods, the child is able to accomplish and absorb great learning feats with an ease and passion that are unavailable later in life (M. Montessori, 1966; The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008). As one conquest is completed, the child moves onto the next one, creating a constant pattern of learning and enjoyment (M. Montessori, 1966; Zener, 2003). The child’s sensitivities result in strong interests for some things and a great indifference to others (Zener, 2003): “When a particular sensitiveness is aroused in a child, it is like a light that shines on some objects but not on others, making of them his whole world” (M. Montessori, 1966, p. 42). Joy and excitement in learning become manifest during these times, fuelled by the child’s surroundings and the adults that encourage and assist in this learning. These sensitive periods prepare the child’s mind to absorb and process the world surrounding them, complementing the ‘absorbent mind’ (Zener, 2003).

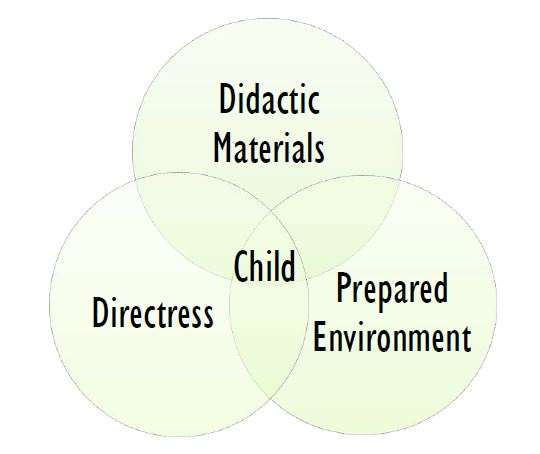

Strong correlations have been drawn between Montessori’s sensitive periods and Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development. In both approaches, the teacher observes the child to provide learning experiences that meet the needs and learning requirements of the child at that point in time (Mooney, 2013; Vettiveloo, 2008). However, Vygotsky believed that this support to a child’s learning does not just come from a teacher, but also from peers (Mooney, 2013). Such learning can be seen in Montessori classrooms with the combined age groups (and now in mainstream early education centres as well).

If you have any questions or comments about any of my blog posts, please don’t hesitate to contact me!

Reference List

Grazzini, C. (1979). Characteristics of the child in the elementary school. AMI Communications, 29–40.

Montessori, M. (1966). The Secret of Childhood. (M. J. Costelloe, Ed.). New York: Ballantine Books.

Mooney, C. G. (2013). Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky (2nd ed.). Minnesota: Redleaf Press.

The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2008). The timing and quality of early experiences combine to shape brain architecture.

Vettiveloo, R. (2008). A critical enquiry into the implementation of the Montessori Teaching Method as a first step towards inclusive practice in early childhood settings specifically in developing countries. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 9(2), 178–181.

Zener, R. S. (2003). How sensitively timed are sensitive periods? The NAMTA Journal, 28(1), 20–40.