At Montessori’s first international training course in 1913, she described the restricting social conditions for children at the time (Feez, 2013). She presented the attendees with the notion of freedom with limits, describing the materials and conditions of her methods, as well as the way a Montessori directress should interact with individual children and their needs (Feez, 2013; Kramer, 1988; Montessori, 1912; Simons & Simons, 1984). Twenty-first century Montessori student teachers still follow a very similar course of topics to that of the first lectures, and her material presentations are just as appealing to modern day children across the globe (Feez, 2013). Feez (2013, p. 108) declared that Montessori training has the same effect now as it did back then in that it “… has a lasting influence on the way people interact with children, and prepare learning environments for them, no matter the context and prevailing wisdom.”

Although Montessori’s influence was starting to decline in educational leadership circles in the late 1930s, there were some diligent believers who quietly continued their work, such as Norma Selfe (Feez, 2013). There were also still Australians travelling to Rome to learn from and participate in Montessori’s training courses (Feez, 2013). Aside from kindergarten and state infant school teachers, some of the teachers who worked alongside Lillian de Lissa and Martha Simpson were known to have continued their work in the Montessori education field (Feez, 2013). Furthermore, some Montessorians opened private schools across Australia, or were involved in the areas of child health or religious orders (Feez, 2013). Some of these known or significant contributors are described further by Feez (2013). Moreover, Feez (2013) declared the work of these dedicated Australian Montessorians made an impact internationally from the beginning.

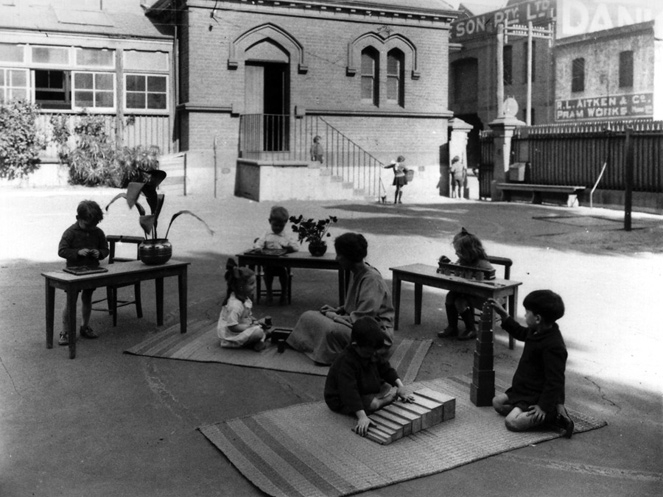

Feez (2013, p. 14) marvelled that “… for over a century, and across the world, the Montessori approach has resisted obsolescence, making it an oddity among the educational choices available to parents and teachers today.” In the Montessori schools of the past and present, children are taught how to be independent contributors to society, where this independence is the foundation of their freedom (Feez & Sims, 2014; Kramer, 1988; Montessori, 1912; Simons & Simons, 1984) and where children are “… free to follow their true nature and to learn through their own effort.” (Feez, 2013, p. 15). Children are considered active learners, understood to be developing in a series of stages, through use of a specially designed environment to assist their progression (Feez, 2013; Kramer, 1988; Montessori, 1912; Simons & Simons, 1984). Furthermore, that exploring a concept first in its concrete form is vital for foundational learning (Kramer, 1988; Montessori, 1912; Simons & Simons, 1984). These ideas can still be seen in a variety of early childhood settings today, whether Montessorian or not (Simons & Simons, 1984). Children are being given more choice in their basic educational needs, and their development through learning stages recorded in detail. This idea of observing a child’s development stems from Montessori’s scientific observations she employed during her time as a medical student (Feez, 2013; Kramer, 1988; Simons & Simons, 1984).

It was Montessori’s belief that these observations were the basis of a Montessori teacher’s work (Feez, 2013; Montessori, 1912). Montessori thought that observing children in the strict, traditional settings of the past could not uncover the truth of each child (Feez, 2013; Montessori, 1912). However, some of the more detailed methods for observing children’s development from the original 1913 training course are no longer used (Feez, 2013). These incredibly precise analyses arose from Montessori’s medical experience at the University of Rome’s Psychiatric hospital (Feez, 2013; Kramer, 1988). They were, however, ground-breaking at the time in that they focussed the educator’s attention on children’s developmental and social needs, presaging the way twenty-first century educators plan individualised learning programs across a diverse range of educational fields and age ranges (Feez, 2013; Simons & Simons, 1984).

Possible reasons why the Montessori approach is not more widespread in Australia

Social conditions during the depression worsened, resulting in increases of infant and maternal mortality, poor health and sanitation, unemployment, homelessness, and overcrowding (Feez, 2013). Free kindergartens and infant schools became safe places where children received care as well as an education (Feez, 2013). Feez (2013) noted that the disparity between infant schools and kindergartens became hard to differentiate between at this time as well, so phrases such as early childhood education and preschool became more evident. However, Feez (2013) also acknowledged that there was still a distinct separation between education and childcare. Due to the severity of social and financial conditions, these centres had to reduce staff and resources, which Feez (2013) posited could be a reason for the decline in the Montessori vs. Froebel debate, and the popularity of both.

When the 1937 international New Education Fellowship Conference was held in Australia, the most popular papers and presentations were by “… the new leaders of the progressive education movement, the educational psychologists and psychoanalysts promoting play as the basis of children’s intellectual and social development” (Feez, 2013, p. 107). Although the start of the New Education Fellowship in 1921 was originally inspired by Maria Montessori, and 1937 was the Froebel centenary, there was not much interest shown in either of these educational fields at the conference (Feez, 2013).

Feez (2013) also identified a shortage of trained Montessori teachers as a significant limiting aspect for Montessori education’s reach. She links this to “… the tyranny of distance …”, made worse by teachers leaving the unstable working conditions of small schools for greater security in their careers (Feez, 2013, p. 134). Moreover, Simons and Simons (1984) posited that Montessori teacher training is not up to modern standards of teacher education. This limitation could possibly deter people from undertaking the training. Additionally, Murray (2008) declared that access to Montessori teacher training is limited.

While access to pure Montessori education is still somewhat limited for families in twenty-first century Australia, there seems to be a resurgence in some of its principles, which Lillian de Lissa already remarked upon in 1955 (Feez, 2013). On reflection of the educational ideas of the past, she observed that rather than being outdated, they could have been understood as radical and enlightened thought if worded in more modern phraseology (Feez, 2013). However, it can still be difficult for parents to identify the degree to which a centre is Montessorian, adding to the confusion about what Montessori education actually is (Murray, 2008).

Lastly, limited or misinterpreted understanding of the true nature of Montessori education is another possible limitation (Murray, 2008). Analyses of Montessori education by Simons and Simons (1984) outlined many misunderstandings that are often stated in regard to the field. For example, they argued that the “… classroom environment is frequently impoverished, rigid, and rule-bound” and that “music, dance, drama, literature, and poetry are neglected” (Simons & Simons, 1984, p. 44). This narrow idea that Montessori education is too suffocating of children’s creative potential seems to be a common view in modern society.

Summary of Parts 1 and 2

Montessori’s ideas had a significant impact on Australian education in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The concepts of liberty, freedom and independence appealed strongly to the post-invasion, democratic Commonwealth ideals of Australia’s past. The advocacy of a few sparked a tidal wave of educational reform that gradually diminished with the rise of progressive New Education after the war. However, her philosophies continue to influence early childhood education today, whether in Montessori classrooms or otherwise. While there is still limited access to pure Montessori primary and secondary schools, there appears to be increasing interest in Montessori early childhood education. Whether there is a resurgence or not, Dr Maria Montessori left a legacy that changed Australia’s educational history for good.

Reference List

- Feez, S. (2013). Montessori: The Australian Story. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

- Feez, S., & Sims, M. (2014). The Maybanke Lecture 2014 (pp. 1–58). Sydney: Sydney Community Foundation.

- Kramer, R. (1988). Maria Montessori: A Biography. Chicago: Da Capo Press.

- Montessori, M. (1912). The Montessori Method. English (American E.). Radford: Wilder Publications.

- Simons, J. A., & Simons, F. A. (1984). Montessori and Regular Preschools: A Comparison. Urbana.