Montessori’s planes of development came from her medical observations where she identified four clear stages of human development from conception to maturity (Grazzini, 1979; Haines, Baker, & Kahn, 2000; M. Montessori, 2012; Stephenson, 1991). Each plane spans six years with developmental similarities identifiable between the first and third planes, and the second and fourth planes (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000; M. Montessori, 2012; Stephenson, 1991). The four planes were then subdivided into sub-planes of three-year periods (M. Montessori, 2012). She described the first and second planes as the childhood stage (‘infancy’ then ‘childhood’), and the third and fourth planes as the adulthood stage (‘adolescence’ then ‘maturity’) (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000; Stephenson, 1991). Grazzini (1979) noted that although each plane and its characteristics are unique, each plane also prepares for the following one, creating an “arc of human development” (p. 30). Montessori wanted these planes of development to be viewed not as a teaching curriculum but as supports to life, as something that assists the child “… to help it help itself become itself” (Stephenson, 1991, p. 15). Montessori explored the characteristics used by humans to cultivate themselves, identifying significant tendencies from the various planes.

The first plane (infancy) – zero to six years of age

The human in this plane is constructing its individual self, requiring assistance from others (usually adults) to create itself (M. Montessori, 2012; Stephenson, 1991). Montessori used the phrase absorbent mind to describe the intellect of a small child, where the mind moves from unconscious ‘absorbency’ in the first sub-plane (0-3 years of age) to conscious in the second (3-6 years of age) (M. Montessori, 2012; Stephenson, 1991). Section 4 discusses the absorbent mind further. The first plane is where the child absorbs and processes its environment, then explores and orders it—where intelligence is formed (Haines et al., 2000; M. Montessori, 2012). It is where the foundations for the child’s personality are laid and constructed for the following years of life and learning through experiences and social relationships (Haines et al., 2000; M. Montessori, 2012; Stephenson, 1991).

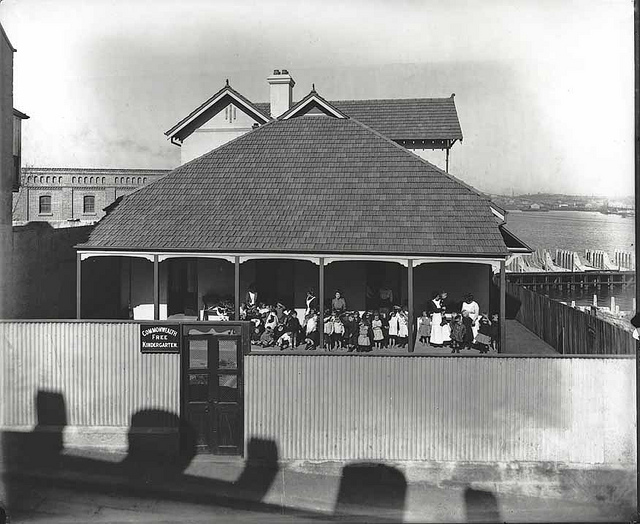

The first steps toward social development are taken during this time, with the first ‘social environment’ encountered being the maternal care of the mother (Haines et al., 2000). This encounter is vital both for the physical and social development of the child (Haines et al., 2000). The young child becomes like a sponge, absorbing behaviours, culture, and language through interactions with the parents and the family (Haines et al., 2000). Once the child reaches the age of 3 years, wider social interactions are required for further learning—that of their peers (Haines et al., 2000). Through these interactions with peers and the formal education environment, the child develops vital intellectual, social, moral, and physical skills (Haines et al., 2000). Montessori recognised the importance of having mixed ages in her classes because it “… fosters self-discipline, independence, and responsibility …” (Haines et al., 2000, p. 4) where the younger children learn from the older children, and the older children develop greater levels of responsibility and leadership.

The second plane (childhood) – six to twelve years of age

Grazzini (1979) described four facets of the psychological development of a child in this plane: 1) intellectual; 2) moral; 3) social; and 4) emotional. These areas were also explored by Haines, Baker, and Kahn (2000). These facets work together in the development of the whole child (Haines et al., 2000) but Grazzini (1979) noted that it can be useful to discuss them separately to comprehend them better.

Intellectual

During the second plane, Montessori recognised two sensitive periods with regard to intellectual characteristics: imagination and culture (Grazzini, 1979). Furthermore, the child has a fascination in and propensity for the abstract, interested in the how and the why of the world, and developing an understanding of cause and effect (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000). Grazzini (1979) refers to ‘creative imagination’ where the child’s mind creates new connections from reality, resulting in new patterns and ideas. They wish to understand things for themselves instead of accepting facts at face value (Haines et al., 2000). This creative imagination manifests in a child’s curiosity about the world and in the tiny details to be found within it (Grazzini, 1979). Montessori stated that imaginative vision has no limits so it is therefore vastly dissimilar to the perception of something concrete (Grazzini, 1979). Whilst a ‘concrete approach’ was utilised in the first plane, in the second plane the child uses a concrete approach to abstract concepts (Haines et al., 2000).

The second intellectual sensitive period of this plane was that of culture. Montessori (2012) described imagination and culture as being intrinsically linked, because “… culture is not made up of the knowledge of things seen” (p.155). We need our imagination to fully understand and appreciate culture. She gave the example of Geography, where the person must imagine snow if they have never been to a place that has it (Montessori, 2012). It is during the second plane that enthusiasm and interest in science and culture blossoms (Grazzini, 1979; M. Montessori, 2012). The child in the second plane has moved on from absorbing the immediate environment, and is now wanting to understand the wider world and how it affects life, building on the knowledge developed in the first plane (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000; M. Montessori, 2012). The child begins to understand the interconnectedness of living things, “… the ‘cosmic task’ of each element and of each force in the cosmos, including our human society” (Grazzini, 1979, p. 35).

Montessori believed that culture cannot be obtained from another, but from individual work and improved understanding of the self (Haines et al., 2000; M. Montessori, 2012). It is here that Montessori’s cosmic education comes into play. Mario Montessori (1976) believed that she developed cosmic education through her use of her imaginative vision to connect the past and present. Montessori’s concept of cosmic education explores humanity’s relationship to the universe (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). Montessori had a profound admiration for creation and believed that humanity’s collective task was to understand the infinite possibilities of creation and to make them apparent in innovative ways (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). This philosophy influenced her cultural curriculum, where her love and fascination with the sciences and her endless respect for and curiosity about creation is evident.

Moral

Montessori observed that children in the second plane are captivated by ethical life questions (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000). It is during this time that the child questions and evaluates actions, with this sensitivity for morality informing their development of social relationships (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000). Furthermore, Montessori identified that the child’s understanding of justice and the connection between a person’s acts and the needs of others are developed here (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000). The child of six to twelve years cultivates their inner moral compass, which, when fixed, clearly displays their moral characteristics (Grazzini, 1979; Haines et al., 2000). Grazzini (1979) compares these moral characteristics to humanity’s virtues of justice, fortitude, and charity.

Social

Mario Montessori (1976) observed that children in the second plane have an increasing fascination in their peers’ behaviours, and have a greater desire to join others in groups. They view adults differently, idealizing ‘heroes’ and role models, with a new outlook of the world beginning (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). The children of this age often mimic their peers, and cultivate a system of sharing and taking turns not seen in the first plane (Grazzini, 1979). This fascination with peers results in the child forming strong relationships with other children, and preferring their company over that of family (Grazzini, 1979). This strong connection with peers gives rise to a willingness to abide by strong social rules within the group but a resistance to wider rules and disciplines as used in school (Grazzini, 1979).

Haines, Baker, and Kahn (2000) identify social development as part of the creation of personality in how people interact. During the second plane they question culture, society, and relationships, and start to understand their part in the world. The child must live in a social context and therefore adapts to the surrounding human culture (Haines et al., 2000). It is during this plane that the child becomes interested in things other than themselves, and consequently develops more of an affection for and understanding of humanity through knowledge of history (Haines et al., 2000). Through these aspects of knowledge acquisition, the child learns how the actions of an individual affects others (Haines et al., 2000). As such, Montessori advocated self-discipline and character development alongside educational development in this stage (Haines et al., 2000).

Emotional

Grazzini (1979) stated that the emotional aspect of the child aged six to twelve years is interconnected with the previously mentioned characteristics of the plane. The child of this plane often loses some of the ‘sweetness’ or ‘affection’ seen in the previous plane, leaning more towards a strong sense of independence and a thirst for knowledge which can sometimes manifest itself in ‘rudeness’ (Grazzini, 1979). Having said that, the child of this age is also more sensitive to the opinions or negative comments of others. During this time the child is developing their own sense of worth, with a longing for praise and acknowledgement from adults and peers alike (Grazzini, 1979). Grazzini (1979) quoted Mario Montessori in noting that once the child has gained his own self-respect and is sure of himself he becomes calmer and self-possessed, and is less likely to rebel against parental authority. This self-possession and calm are evident in Maria Montessori’s descriptions of the child of this plane as having mental and physical stability (Grazzini, 1979).

The third plane (adolescence) – twelve to eighteen years of age

Like the first plane, the third is recognised as a plane of creation (Grazzini, 2004). The child in the first plane is creating a human being, while the individual in the third is creating an ‘adult’ with the abilities to continue the species (Grazzini, 2004). It is at this point that the child enters adulthood, moving through puberty in the physical sense, and transitioning from living in a family to living in society in the psychological sense (Grazzini, 2004). The individual’s sense of justice and personal dignity is developed during this plane, although the physical changes the individual endures can result in emotional, physical and intellectual difficulties of a temporary nature (Grazzini, 2004). Montessori created a proposal for secondary education to support the individual of the third plane to be economically independent, bolster self-confidence, provide assistance during the difficult physical transformations, and encouragement for the entrance into wider society (Grazzini, 2004).

The fourth plane (maturity) – eighteen to twenty-four years of age

The final plane of Montessori’s theory is that of the university-aged individual. This individual has been ‘formed’ over the previous three planes, with a “… spiritual strength and independence for a personal mission in life” (Grazzini, 2004, p. 37). The individual of this plane should have achieved a high level of morality and conscientiousness, being willing to work whilst studying to gain economic independence and ethical stability (Grazzini, 2004).

Reference List

Grazzini, C. (1979). Characteristics of the child in the elementary school. AMI Communications, 29–40.

Grazzini, C. (2004). The Four Planes of Development. The NAMTA Journal, 29(1), 27–61.

Haines, A., Baker, K., & Kahn, D. (2000). Optimal Developmental Outcomes: The social, moral, cognitive, and emotional dimensions of a Montessori education.

Montessori, M. M. J. (1976). Education for Human Development: Understanding Montessori. New York.

Stephenson, M. E. (1991). The first plane of development. AMI Communications, 14–22.