Howard Gardner’s research about the Multiple Intelligences of how children learn has been utilised extensively in education. He argued that intelligence is an extensive array of skills and knowledge rather than a unitary IQ (Vardin, 2003). Maria Montessori and Gardner both challenged the general views of their respective eras about intelligence and potential, coming to similar conclusions but with different foci (Vardin, 2003). Theorists such as they influenced the educational frameworks that are used today, as seen in the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF).

How Montessori principles of educating the ‘whole child’ relate to theories of ‘Multiple Intelligences’ and the EYLF

Gardner believed that humans process the information gathered in cultural settings to make valuable contributions to that setting (Vardin, 2003). He understood intelligences to be ‘potentials’ that are used or activated as needed in accordance with the standards of the surrounding culture, the opportunities available, and the decisions to be made therein (Vardin, 2003). Gardner used regular observations of people to gather his research, just as Montessori did (Kramer, 1988; O’Donnell, 2007; Röhrs, 2000; Standing, 1957; Vardin, 2003). They both observed people with special needs and those considered ‘normal’, allowing them to gain better understandings of the variety of human capabilities and to challenge the limited views of the time about these abilities (Kramer, 1988; O’Donnell, 2007; Röhrs, 2000; Standing, 1957; Vardin, 2003). Montessori and Gardner recognised that each child is an individual, with unique personality traits becoming evident in the early years of life (Montessori, 1912, 1966; Vardin, 2003). Gardner argued that each person has their own combination of intelligences, and as such, each person should be appreciated for their unique personality and what they can contribute to society (Vardin, 2003). Recognising and valuing these differences is central to his theory of the Multiple Intelligences.

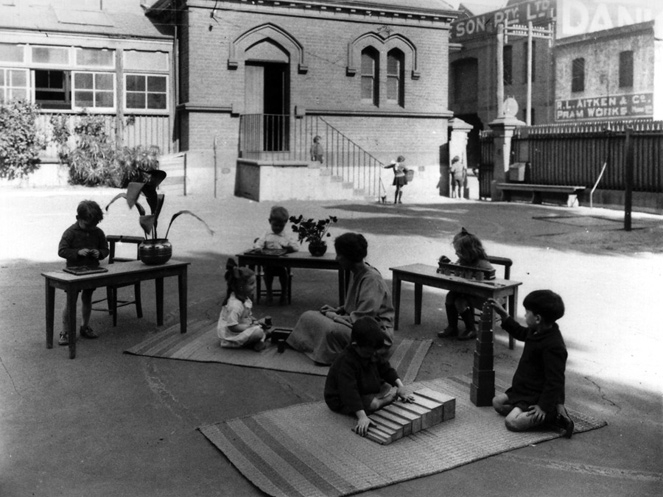

Montessori and Gardner alike recognised that children have a natural inclination to learn. They believed that the child’s innate interest and ability to learn comes from a genetic base, but that continuing development is the result of a continuous and vibrant relationship between the child’s genetics and the influence of the surrounding environment (Haines, Baker, & Kahn, 2000; Vardin, 2003). It was Montessori’s understanding that the child absorbs information from the surrounding environment, which can be seen in her theories about the absorbent mind (Montessori, 1912, 2012; Vardin, 2003). Both theorists recognised the significance of the environment in its influence over the child’s development, whether that be its positive or negative effects (Haines et al., 2000; Vardin, 2003). Gardner argued that even those considered gifted will not flourish if their environment did not provide the resources, interventions, and materials to encourage their intelligence to develop (Vardin, 2003).

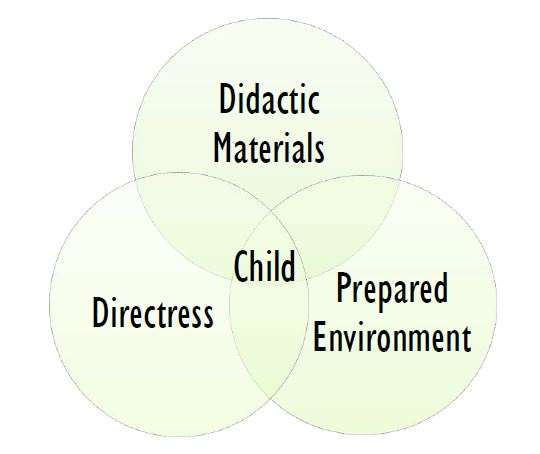

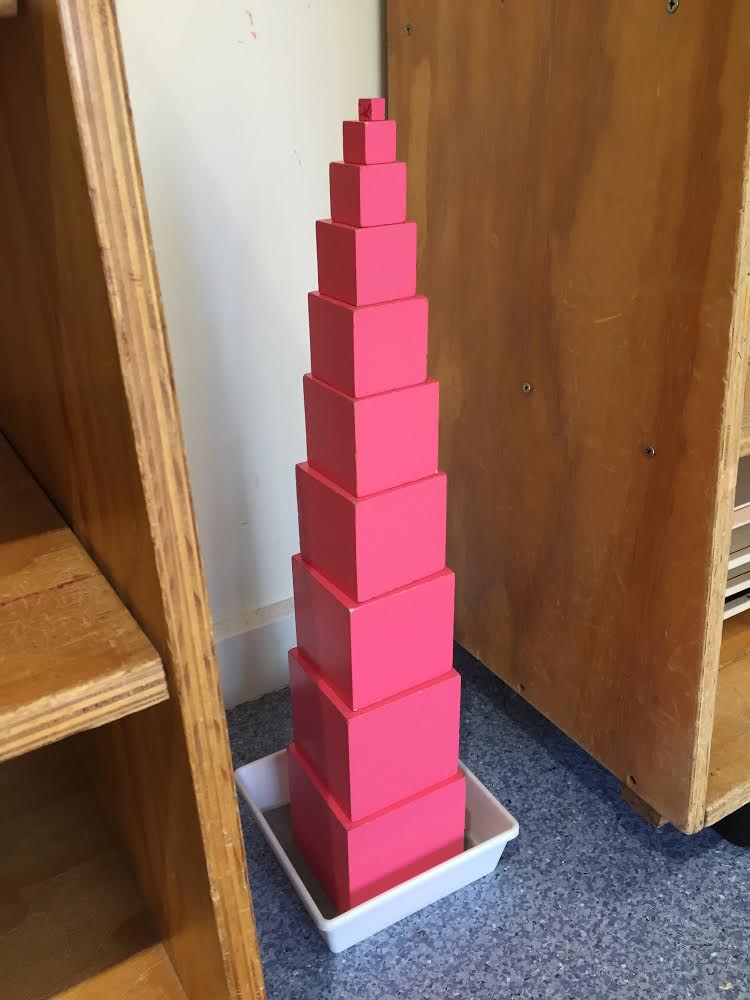

While Montessori and Gardner share some viewpoints of education and development, their work foci differ (Vardin, 2003). Montessori’s main focus from the start of her educational career was that of the welfare and education of children with special interests in the poor or the overlooked (such as those with special needs) (Kramer, 1988; Montessori, 1912; Standing, 1957; Vardin, 2003). This focus is evident in her approach to education, her didactic materials, teacher and parent training, and her method of teaching. Her work influenced her philosophy and methodology, both of which then influenced her educational practice. Gardner’s work, on the other hand, was theoretical. His theories were derived from his observations and research, not from practice (Vardin, 2003). He did not have an educational approach that he created based on his theories, instead believing that educators should use his research to inform their practice for the betterment of the children (Gardner, 1995; Vardin, 2003).

Gardner’s research focused on the areas of human potential that he defined as intelligences. He took moral and spiritual characteristics into consideration but did not consider them to be part of his Multiple Intelligences as they did not meet his criterion (Vardin, 2003). Conversely, Montessori’s theories encompass all aspects of the child’s nature. This includes the moral and spiritual characteristics, as she viewed the human tendencies and potentials as parts of the ‘whole child’ (Haines et al., 2000; Vardin, 2003). She recognised the importance of each aspect of the child, and designed her materials and environments to support the development of all of these human potentials and tendencies (Haines et al., 2000; Vardin, 2003). Consequently, her materials also correlate with the core operations of Gardner’s intelligences. Vardin (2003) gives the example of a lesson with Montessori’s geometric solids where the child:

… uses a bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence in feeling the forms, visual/ spatial in observing and internalizing images of the forms, logical-mathematical intelligence in establishing relations between them, naturalistic intelligence in observing and classifying them, and linguistic in labelling them. If the child did this activity with other children, he or she could also exchange ideas about the forms and share them, thus utilizing interpersonal intelligence. (Vardin, 2003, p. 43)

Vardin (2003) went on to explain in detail how Montessori’s curriculum areas connect to Gardner’s eight intelligences and their core operations. She acknowledged how Montessori explored the social and emotional characteristics of the child as well, including the value of self-regulation and self-knowledge (Vardin, 2003). Vardin (2003) stated that Gardner and Montessori were innovative individuals of their times, paving the way for greater understandings of how people learn and the potential they have within.

The research done by theorists like Montessori and Gardner influenced our current understandings of how children learn and develop. Montessori’s concept of educating the ‘whole child’ is evident in Australia’s Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR), 2009). The document recognises the significance of each facet of the child in their development, with the concepts of belonging, being, and becoming central to its holistic philosophy (DEEWR, 2009). Its vision for children’s learning is that “[a]ll children experience learning that is engaging and builds success for life” (DEEWR, 2009, p. 7). It takes into account all aspects of a child’s learning journey, not simply focusing on academics. It recognises that all children bring unique experiences and knowledge to their learning, and that all areas of their learning are intrinsically linked (DEEWR, 2009). Like Montessori, the EYLF acknowledges that children are active participants in their own learning, and that understanding and utilising this participation will allow educators to transcend limited preconceived ideas about how children learn (DEEWR, 2009).

Evidence shows that educating the whole child through recognising the interconnectedness of education and care is the most beneficial path for the child (Browning et al., 2002; DEEWR, 2009; Edwards, 2002; KidsMatter Early Childhood, 2011; Montessori, 1912; Rushton, 2011). When understanding the child as a whole, taking into account body, mind, and spirit, the educator facilitates learning experiences for all aspects of the child’s present and future life (DEEWR, 2009; KMEC, 2011; Montessori, 1912; Rushton, 2011). From a neuroscience perspective, Rushton (2011) argued that “… any developmentally appropriate program focuses on the ‘whole child’” to benefit the child’s “… mental, emotional, social, and physical life …” (p. 92). Once again, this proves that Montessori was ahead of the times in recognising the significance of holistic development. DEEWR (2010) stated that the Practices and Principles of the EYLF are based on the conviction that “learning is dynamic, complex and holistic” (p. 14), as can be seen in the works of Montessori (Montessori, 1912, 1966). Furthermore, both Montessori and the EYLF identify the significant role of the learning environment in a child’s development. The EYLF describes constructive learning environments as those that are welcoming, vibrant, flexible, and responsive to the child’s needs (DEEWR, 2009). This view of the learning environment mirrors that of Montessori’s, where it is understood to be the second teacher, a living environment that is adapted to the needs of the children (Montessori, 1912; Röhrs, 2000). Due to the similarities, Australian Montessori educators have the opportunity of blending these two brilliant tools for educating young children with best practice—the EYLF and the Montessori method.

Reference List

Browning, K., Mugyeong, Eunseol, K., Ock, R., Nary, S., Moon, … Weikart, D. P. (2002). Curriculum in Early Childhood Education and Care. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 3(2), 81–87.

Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations. (2009). Belonging, Being & Becoming: The Early years Learning Framework for Australia (Vol. 1). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations. (2010). Educators ’ Guide to the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Edwards, C. P. (2002). Three approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori, and Reggio Emilia. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 4(1).

Gardner, H. (1995). Reflections on Multiple Intelligences: Myths and Messages. Phi Delta Kappan, 77(3), 200–209.

Haines, A., Baker, K., & Kahn, D. (2000). Optimal Developmental Outcomes: The social, moral, cognitive, and emotional dimensions of a Montessori education.

KidsMatter Early Childhood. (2011). KidsMatter Early Childhood Connecting with the Early Childhood Education and Care National Quality Framework.

Kramer, R. (1988). Maria Montessori: A Biography. Chicago: Da Capo Press.

Montessori, M. (1912). The Montessori Method. English (Second). New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Montessori, M. (1966). The Secret of Childhood. (M. J. Costelloe, Ed.). New York: Ballantine Books.

Montessori, M. (2012). The Absorbent Mind. California: BN Publishing.

O’Donnell, M. (2007). Maria Montessori. (R. Bailey, Ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Röhrs, H. (2000). Maria montessori (1870-1952), XXIV(1), 1–12.

Rushton, S. (2011). Neuroscience, Early Childhood Education and Play: We are Doing it Right! Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(2), 89–94.

Vardin, P. A. (2003). Montessori and Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Montessori Life, 40–43.