Maria Montessori designed her manipulative materials to meet specific developmental needs of children as they progress through the sensitive periods of development. These sensitive periods are also recognised in current research on brain development. Furthermore, Montessori’s holistic and child-focused perception of education and learning corresponds with the expectations and requirements of the National Quality Standard (NQS) and the Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF). As such, Montessori’s method is still applicable and relevant to the education of children today.

Important attributes of Montessori manipulative materials

All of Montessori’s manipulative materials are designed to teach or introduce an abstract concept in a concrete way. This visual, sensory, and hands-on approach to learning enables the child to explore the materials in a way that is appropriate for their developmental stage (Chisnall & Maher, 2007; Kramer, 1988; M. Montessori, 1912). Each material has a relationship with later materials in some way, building on what was learnt with one activity with another later on (Chisnall & Maher, 2007; M. Montessori, 1912). The Sensorial curriculum covers all the senses—tactile, gustatory, auditory, thermal, baric, chromatic, olfactory—providing the child with a rich array of learning experiences to teach a love of learning and develop all aspects of the brain’s capabilities (Chisnall & Maher, 2007; M. Montessori, 1912).

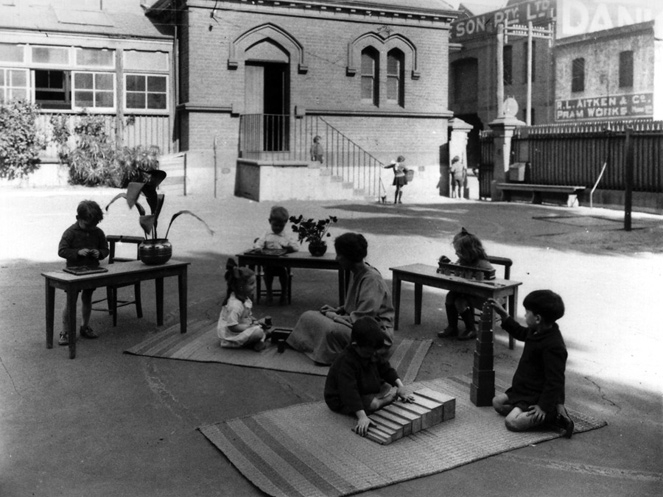

To develop the brain’s potential, Montessori’s manipulative materials have several specific features. These features allow the child to work with the materials without much input from an adult, enabling them to explore and learn at their own pace with control over their own learning (Chisnall & Maher, 2007; M. Montessori, 1912). The materials have an in-built control of error so that the child can see if the activity is completed incorrectly (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). For example, if the brown stairs are not graded correctly, the stair appearance will not be achieved. Isolating a single quality aids the child to focus on that quality and not be distracted by other features (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). The colour of the brown stairs, pink tower, or knobless cylinders remains the same whilst the size changes, as size differentiation is the lesson being taught. The Montessori materials require active involvement rather than passive observation (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). Movement, spatial awareness, problem solving, and gross or fine motor skills combine to assist in learning. Finally, the materials are attractive to the child, with mathematical proportions that are aesthetically pleasing, uniformity of beautiful colours, and colour coding that also assists with organisation (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007).

The Montessori manipulatives prepare the child’s mind for academic thought and processing through teaching the child’s senses to isolate a characteristic and hone their observation skills (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). They improve thinking, problem solving, and visual discrimination skills through distinguishing, organising, sorting, classifying, and matching (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). All of these activities are preliminaries for reading, writing, and mathematics, preparing the mind for the sensitive periods of these learning opportunities (M. Montessori, 1912; Morrison, 2007). The materials provide “feedback” to the child, with the patterns and solutions stored in memory to be utilised by the child’s imagination in the form of new ideas and answers (Chisnall & Maher, 2007). Montessori designed these materials to be a link between concrete experience and abstract thought and reasoning, better to absorb learning (Chisnall & Maher, 2007; Kramer, 1988; M. Montessori, 1912). Furthermore, she designed her materials to assist the child in the development of their personalities into “… mature and independent adulthood” (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 31).

Mario Montessori believed that this last aspect of the Montessori materials is usually disregarded when considering their attributes (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). He explained that some believe the Montessori materials are considered too rigid to assist in the unconstrained development of the child’s personality, while others view them as limited and deficient in meticulous systemisation (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). However, Mario recognised that the Montessori materials play a significant role in children’s learning through. He identified two main purposes of the materials—to extend the child’s internal development and to assist the child to obtain new understandings of the world through exploration (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). They sharpen the child’s powers of observation and how to use this gathered information, and he believed that each material also “… challenges the intelligence of the child, who is first intrigued and later fully absorbed by the principles involved” (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 36). Once the principle has been internalised and mastered by the child, they then apply this knowledge to the use of other objects (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976). Mario Montessori goes on to identify the “guiding instincts” or “inner directives” that drive humans to learn and progress, linking them to the sequences (or developmental planes) of development and maturation (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 33). Moreover, he highlights Montessori’s theory of “the absorbent mind” as a developmental tool that children are equipped with but adults are not (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 33). He highlighted that the materials do not teach the “factual knowledge” but rather enable the child to recognise their own knowledge, which in turn expands the child’s faculty for additional learning (M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 36). Consequently, Maria Montessori named this process “materialized abstractions” (Haines, Baker, & Kahn, 2000; M. Montessori, 1912; M. M. J. Montessori, 1976, p. 36; Röhrs, 2000).

Reference List

Chisnall, N., & Maher, M. (2007). Montessori mathematics in early childhood education. Curriculum Matters, 3(23), 6.

Haines, A., Baker, K., & Kahn, D. (2000). Optimal Developmental Outcomes: The social, moral, cognitive, and emotional dimensions of a Montessori education.

Kramer, R. (1988). Maria Montessori: A Biography. Chicago: Da Capo Press.

Montessori, M. (1912). The Montessori Method. English (Second). New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Montessori, M. M. J. (1976). Education for Human Development: Understanding Montessori. New York.

Morrison, G. S. (2007). Early Childhood Education Today. Early childhood education today (Tenth). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Röhrs, H. (2000). Maria montessori (1870-1952), XXIV(1), 1–12.